In Praise of Liminal Space —

Notes on Istanbul’s Continuous Wall

May 2024, Lausanne, published in L’Atelier magazine, EPFL

My inquiry started with a copy of a late 15th century map from the liber insularum archipelagi by Cristoforo Buondelmonti which depicts Constantinople through selected topological and geographical elements. The fabric of the city, i.e. the streets, the built plots, the squares, is absent from the representation. Blank space. Instead, the city is abstracted through an allegory of its religious and political authority embodied respectively in Hagia Sophia and its defense walls. (1) Both the Hagia Sophia and the Theodosian Walls remain defining features of Modern Istanbul, despite the city’s tumultuous past and fast changing political tides. While the Hagia Sophia has been the subject of much debate on its design or religious instrumentalization, the Theodosian Walls on the other hand are often overlooked, although their role in the subsistence of the city is no less important. The multilayered defense system dates back to the 5th century and stretches over 5.5 km across Istanbul’s historic peninsula from the Golden Horn to the Marmara sea.

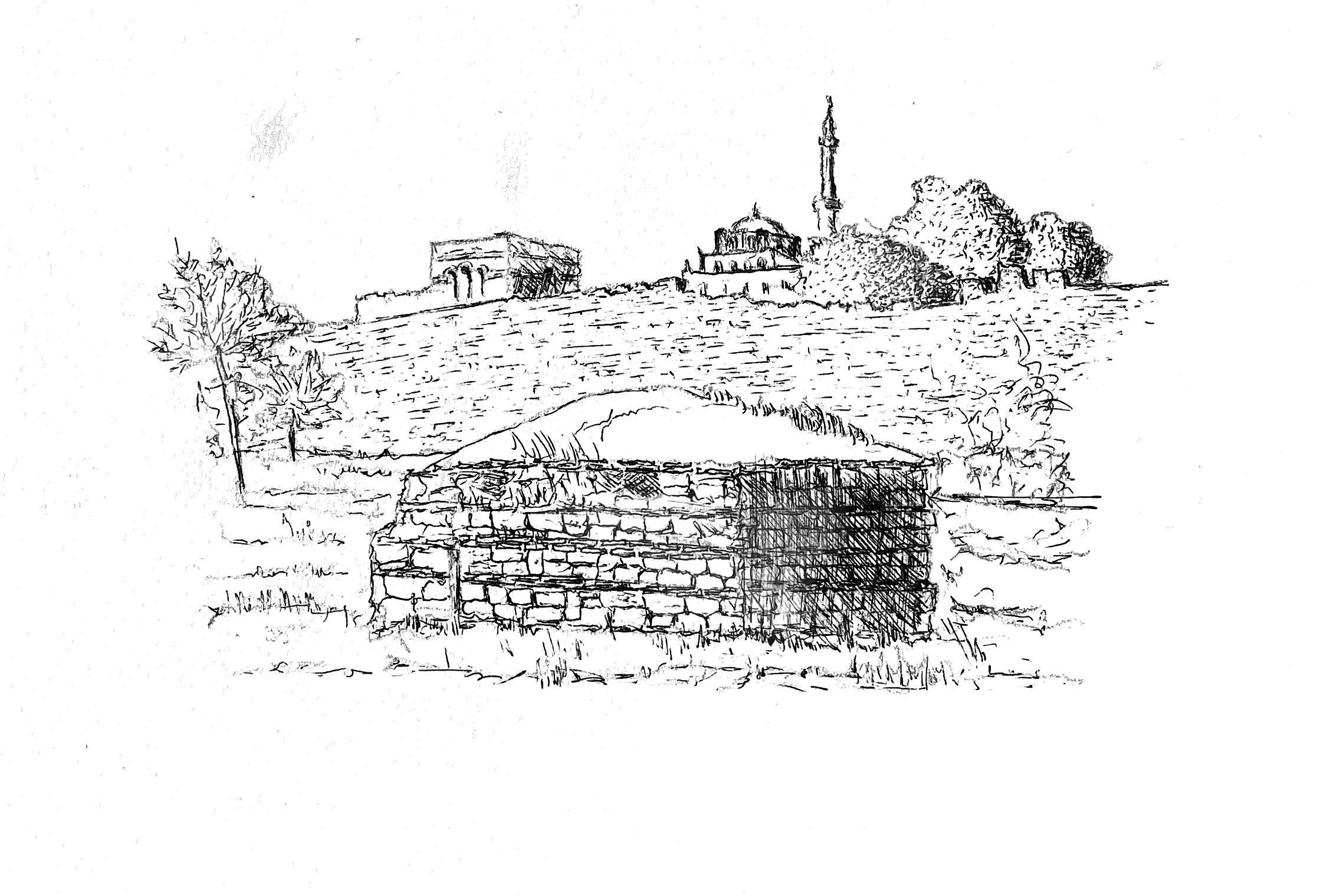

These first observations led me last summer to walk along the Theodosian walls in search of the city’s Byzantine past. What I found instead, was a cross section of its present and a glimpse of its future. I here use the word ‘cross section’ both as the depth of the wall — a line with varying thicknesses based on its state of preservation, topographical setting and porosity, and its breath — a wide variety of uses and landscapes that unfold along the wall’s linear path.

I argue that the nearly uninterrupted physical wall also links Istanbul, with all previous iterations of itself — a time and space continuum, through which the city can be read and understood. More than a monument it is a continuous ‘document’ onto which memories are preserved, manufactured or falsified.

I propose through this short illustrated essay to cast the wall as a methodology to uncover Istanbul's palimpsest. An exploration in zigzag, which renders the wall as a line fixing the form and image of the city, as a surface onto which narratives of the victors are projected, as a space directing flows, uses and customs.

Through this approach the wall is seen as an analogical machine for the city. A structure that binds much more than it divides. A device that captures the city otherwise.

From Furrows to Form

A line in-forming the city

Founded as the New Rome, Constantinople belongs to the tradition of Roman cities. As such, it finds its origin in the establishment of a center (mundus) and a perimeter (sulcus primigenius). The center was symbolically marked by a hole, while the limits were traced by plowing a furrow. (2) Allegedly, Constantine himself traced the perimeter of his new Capital, whose walls were to become the built manifestation of this sacred ritual. From the line in the ground, a wall stands out and gives a form to the city. A form that survived what it meant to protect, which was altered or obliterated by invasions, plundering, great fires and plagues (3) The wall is not indestructible. In fact, of the Constantine wall, almost nothing remains: the Theodosian Wall existing to this day constitutes a larger perimeter. But the wall was constantly maintained and consolidated, not only to function as an effective line of defense but because there cannot exist a Constantinople without its institutionalized form. (4) In other words, not only must the wall retain its physical integrity but must persist as a representation of the city and its rulers. This representation becomes all the more important as the physical form is threatened by political instability or weakening authority. (5) An interrupted trace onto the map, spanning from the Golden Horn to the Marmara Sea, giving the historic peninsula its recognizable triangular shape. Going back to the Liber Insularum and subsequent copies of the 15th century map which have survived up to date, the literal and metaphorical representation of Constantinople seems to be constantly reinterpreted. The dates of these maps coincide with the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople and suggest a bias on the part of Western authors to emphasize the city’s Christian heritage in continuity with the Byzantine tradition. For instance, institutions (churches, mosques, palaces, forums), dwellings and commercial structures are in turn absent from one depiction to another (6). The walls (both land and sea wall) however, are uncontested. They are accurately drawn on every map as a quintessential part of the city’s image. The same importance to map making and the symbolic function of the wall was given by the Ottomans, as a way of legitimizing their power over the city and linking their authority to Roman imperial roots (7). Not only did they maintain the walls of the city and the military infrastructure around them, but also measured and marked the center of the city (today’s historic peninsula) with a rotating porphyry column.

A line as a limit

The wall defines a clear boundary between the city and its productive Thracian hinterland, between civitas, and unruly countryside, between inside and outside. The materialized line is political in so far as it defines specific norms and uses on either side of it. Burials, for example, were conducted extra-muros according to Roman tradition. Although the Theodosian Wall no longer constitutes a perimeter to the city whose modern development in the post-war period has led to unprecedented land use, some practices still endure in continuity with the city’s ancient customs: no less than 40 cemeteries and mausolea populate the strip of land on the wall's outer perimeter. Similarly, the right to call oneself from Constantinople, (by birth or by use) and therefore belonging to the city has constantly been debated. (8) Urban Planning and the city’s capacity to accommodate outsiders has always been contingent on the strength of its political apparatus. The further the Byzantine empire shrunk around Constantinople the further exclusionary the city had become with whom it considered as outsiders. (9) Following the sieges of the 7th century by Slavs, Avars or Arabs the population decreased drastically, allegedly ten-fold by the 13th century compared to its 6th century figure. (10) The surviving population led a very ‘rural’ life inside the city walls, a city reduced to inhabited patches spread across arable lands. (11) The receding city was therefore no longer defined by a ‘project’ but solely through the persistence of the city’s form generated by the walls.

A dotted line

The continuous wall is a selectively dotted line: a line interspersed with gates, allowing passage at certain points in time and space. These points are intersections of varying flows: people, goods, food and water supplies. These flows conversely inform and are shaped by the development of urban infrastructure and programs. Where the walls meet the main thoroughfares, religious complexes (monasteries, mosques, madrasas), markets and baths are found. These older intersections of city life are those onto which new mobility nodes are inserted. For instance, the Topkapi Gate hosts today a large bus terminal on its inner square. Until the early 2000’s, the site on its outer perimeter, today the “culture park” was occupied by the city’s largest bus interchange platform, the point of arrival of buses from Istanbul (innercity), Thrace, and Anatolia. (12) Where the wall meets the aqueducts and water streams, fountains and large cisterns (Cistern of Aetius) are found. They are points of relay and storage in a larger water network including the line of Valens bringing water from surrounding forests (13). Hence the porosity of this line of defense allowed for life and trade to flow in and out of Constantinople, and in turn was transformed by it. The gates of the wall still constitute, to this day, zones of flux, density and activity, even as their doors no longer close.

From Spolia to Simulacrum

A surface as a palimpsest

The land walls of Istanbul are a 5.5 km long scroll on which things are added and erased, attesting or removing the traces of time and the succession of political projects. The very matter of which this palimpsest is made, namely mortared rubble, has been constantly maintained, replaced and reassembled following earthquakes and assaults on the city. The surface too has been the subject of transformations, immediately noticeable and capable of transmitting information like a sign post. As such, the wall surface is made of patterns from end to end: blocks of limestone interspersed with layers of bricks, informing building practices and available materials. Hence, a familiar presence, unmistakable for no other. The surface is adorned with imperial and religious insignia, but also with language pointing to authors of construction and repairs. The displacement of these signs and symbols along the wall surface, and of their spoliation thereof is also a new dialectic composition. The Golden Gate (Altinkapi) for instance, was traditionally the door through which the Emperor coming from Rome entered the city. Legend has it that once Sultan Mehmet conquered Constantinople, the gate was sealed, such that no emperor would ever come from Rome (14). All these retraced operations and manipulations on the wall turn the continuous structure into a ‘document’ of the city.

A surface as a manufactured sign

The Theodosian Walls are treated as a ‘monument’ today for their architectural and historical significance. Its ‘authenticity’ as a monument however can be contested not from its adaptation and transformation as a palimpsest but rather for its occulting as such. Indeed, with the development of the modern city in the rise of the Turkish state, the wall, deprived of its function, produced a void: a physical void created by unused ditches and wall clearance areas but also a void of meaning. The wall, a semantic container of Byzantine origin, could not be turned into a signifier of Turkish nationalist narratives and was left as a result, abandoned until the 1980’s. Only in the ultimate decades was the wall cast by the ruling political party (AKP, President Recep Erdogan’s party) as the symbol of Muslim and Turkish Conquest of the city by the Ottoman army. (15). This ‘manufactured’ history found a new place of production in the Panorama 1453 Museum, completed in 2008, on the site of the aforementioned Topkapi bus terminal. (16) The circular building uses the mass medium of the panorama along with models to depict the 1453 siege of Constantinople. The account is only told from the Ottoman perspective and is suffused with political and religious discourse serving the populist ruling party. (17) The wall becomes a ‘monument’ celebrating the Turkish character of the city. (18) The surface of the panorama projects onto the surface of the wall a political and ideological veneer. This applied surface also takes on a physical manifestation through shabby restoration work performed on heavily damaged wall sections. (19) The newly erected portions visually erase the original surface under a layer of cemented blocks and bricks whose modes of production and intentions diverge from the original. They constitute a forged surface whose only function is rhetorical.

From Non Aedificandi to Neoliberal

An unbuilt space

The wall first and foremost served a military purpose, that is to defend the city from invaders and resist a siege. As such, it is made up of a system of ditches, motes, and terraces along the three rows of walls. The wall holds a void within its own structure: a void that was never really empty, allowing for agricultural practices through Byzantine and Ottoman times that have survived up to this day. These spaces dedicated to food production within the wall system and at its foot are consistent with the reserves of land charted since Roman times as non aedificandi zones for urban farming and in times of warfare as clear space to deploy soldiers, cavalry and artillery. (20) Therefore, the walls did not only enclose built space from invaders but also arable space to feed the city’s population often managed by monasteries which sold their surplus in city markets. (21). Practices that have endured for centuries, still create a thickness on either side of the wall that marks discontinuity in the city’s dense fabric inside and outside the land walls. This rupture is legible programmatically through ‘holes’ - terrains vagues of uncertain use and property rights - industrial facilities or infrastructure - highway interchanges, power plant, gasometer, large city transport depot - or socially driven facilities - sports equipment, parks, and cultural venues. Together these spaces form an ‘infra-city’, that is the infrastructure and services necessary for the modern city to operate. The wall can thus be read as ‘superstructure’ on which the ‘infra-city’ is grafted, not through material agency but rather through a political and cultural agency.

A counter-space

In this last note, I would like to focus on the ‘holes’ inherent to the wall presence for they offer a reading of this built enclosure beyond the power structures that made it emerge in the first place. These holes, although understood as having fixed boundaries dictated by cadastral plans, are islands of a larger archipelago. Indeed, the wall area was known at least since medieval times as a zone of informal settlements. The presence of Roma people in Sulukule near the Topkapi gate has been attested since the 11th century. With the city’s industrialization and rural migration throughout the 20th century, people have been gathering in cavities and ruins, setting up makeshift dwellings and markets operating on the fringes of the bus terminal and benefitting from the transit of travelers through the area. (22) A network of flows, livelihoods and information that trickles through the “holey city” (23) and across the territory attests of the pirate city. (24)

This alternative city is most manifest when it attempts to resist the neo-liberal forces at play. As a matter of fact, the ‘monumentalisation’ of the walls meant turning the surrounding areas into ‘Turkish’ public space and therefore “moral” public space where all marks of immorality were to be removed. The poor were by virtue immoral and their informal dwellings were to be removed. The kültürpark, including the Panorama 1453 Museum mentioned above, can be read as the institutionalization of a space that was becoming out of control. Similarly, the Roma neighborhood at Sulukule was dismantled and its residents evicted for the sake of neo-vernacular homes part of a gated community project. (25) The eviction was administratively justified by the lack of documentation proving community ownership of the land. The 330 families of Sulukule were displaced in 2018, 30 km west of their neighborhood not without resistance. In fact most of them returned to the wall areas that represent not just the land where their ancestors settled but most importantly a central neighborhood close to working opportunities. (26) Subsequent project such as the restoration of the Tekfur Palace, the establishment of the wall parks, and their sports fields are welcome additions to the attractivity and quality of life in the neighborhood but also enact the gentrification of the Theodosian Walls now coveted by the neo-liberal housing market . More than ever, the remaining cavities of undefined space inside the wall form a rempart against capitalist urban space

Conclusion: An analogical machine as a place for emancipation

The wall is a project, a project of enclosure, of defense and of control. But when its primary function does not survive, while its material presence does, the wall introduces the possibility of an emancipatory project, that of understanding implicit relationships, appropriating undefined space, investing it with our imagination. (27).

Walking along the Theodosian Walls does not merely attest to the static object as a scroll through the history of its parts and layers, but also animates the space around it, as visions of the cities past and future.

Walking switches ‘on’ the wall as the oldest ‘analogical’ machine to comprehend Istanbul as a project by capturing images of the city, triggered by the moving subject. As such the wall is a system of relationships established within a chaotic juxtaposition of time and space (28). The wall is a succession of signs pointing to scattered limbs to be arranged in a subjective way. The wall is a line to be re-traced in zigzag to survey the territory. (29)

Despite the great transformations that the city of Istanbul has experienced, its very eclectic parts are still stitched together through the continuous wall. Its permanence contrasts with the perceived ruptures that have been theorized in the study of Constantinople’s history. These times of great transformations may not have been perceived as such by contemporaries (30) The form of inertia that allows the wall to still exist, also related to certain practices that are indexical to the Ottoman, Byzantine, Roman and even Paloechristian city. As such the wall is a great tool for a critique of history.

Last but not least, far from being a ludic space for the bourgeois flaneur or the historian, the wall is also a place of emancipation. A liminal space nesting alternative practices countering the Neo-liberal city and its ‘conquest’ project. The wall as a form of commons, rather than a form of enclosure, offers a new orientation capable of directing our attention to the processes at play and resisting them.

(1) Paul Magdalino, Studies on the history and topography of Byzantine Constantinople, (London: Ashgate, 2007), 10.

(2) Catharina Gabrielsson,. “The Holey City: Walking Along Istanbul’s Theodosian Land Walls” in Deleuze and Architecture (Edinburgh: University Press, 2013), 179.

(3) Albrecht Berger. “Streets and Public Spaces in Constantinople” in Dumbarton Oaks Papers, (Vol. 54, 2020), 172.

(4) Corboz, André, Le territoire comme palimpseste et autres essais. (Besançon: Les Éditions de l’Imprimeur, 2001), 10-20.

(5) Ian. R Manners, “Constructing the Image of a City: The Representation of Constantinopole in Christopher Buondelmonti’s Liber Insularum Archipelagi” in Annals of the Association of American Geographers, (Vol. 87, No. 1, March 1997), 72.

(6) Manners, “Constructing the Image of a City”, 96.

(7) Speros Vryonis Jr. “Byzantine Constantinople & Ottoman Istanbul” in The Ottoman city and its parts: Urban structure and social order. (New Rochelle: A.D. Caratzas, 1991), 14-52.

(8) Magdalino, Studies on the history and topography of Byzantine Constantinople, 153.

(9) Ibid, 160.

(10) Ibid, 18.

(11) Berger, “Streets and Public Spaces in Constantinople”, 172.

(12) Julia Strutz. “Spiriting Away the Bad Urbanite: From the Topkapı Bus Terminal to the Panorama Museum 1453” in Doing Tolerance (Verlag Barbara Budrich, 2020), 136.

(13) James Crow. “Water and the Creation of a New Capital” in Istanbul and water, ed. Ergin, N., Ergin, N., & Magdalino. P. (Peeters, 2015), 119.

(14) Gabrielsson,. “The Holey City”, 171

(15) Strutz. “Spiriting Away the Bad Urbanite”, 147.

(16) Ipek Tureli. Istanbul, Open City: Exhibiting Anxieties of Urban Modernity (Routledge, 2018), 133

(17) Idem

(18) Ibid, 135

(19) Strutz, “Spiriting Away the Bad Urbanite”, 139.

(20) Gabrielsson,. “The Holey City”, 177

(21) Magdalino, Studies on the history and topography of Byzantine Constantinople, 48.

(22) Gabrielsson,. “The Holey City”, 172-179.

(23) Strutz, “Spiriting Away the Bad Urbanite”, 139.

(24) Hakim Bey, TAZ Zone Autonome Temporaire (L’éclat, 1997), 20.

(25) Strutz, “Spiriting Away the Bad Urbanite”, 139.

(26) Ecumenopolis: City Without Limits, directed by Emre Azam, (Kibrit Film, 2011). 1:09:00 https://vimeo.com/493023602

(27) Pier Vittorio Aureli.“Territory” in AA Files (Vol. 76, 2019), 154

(28) Francesco Careri, Walkscapes: Walking as an aesthetic practice. (Culicidae Architectural Press, 2017), 194.

(29) Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities. (Harvest Harcourt Brace, 1996), 85-88.

(30) Paul Magdalino, Constantinople médiévale études sur l’évolution des structures urbaines (Paris: De Boccard, 1996), 11.